Video Demo: https://youtu.be/rOtRAhowq1Y

My final project for CS50x was a python-based application that used computer vision to dynamically generate sound based on the camera subject’s movements.

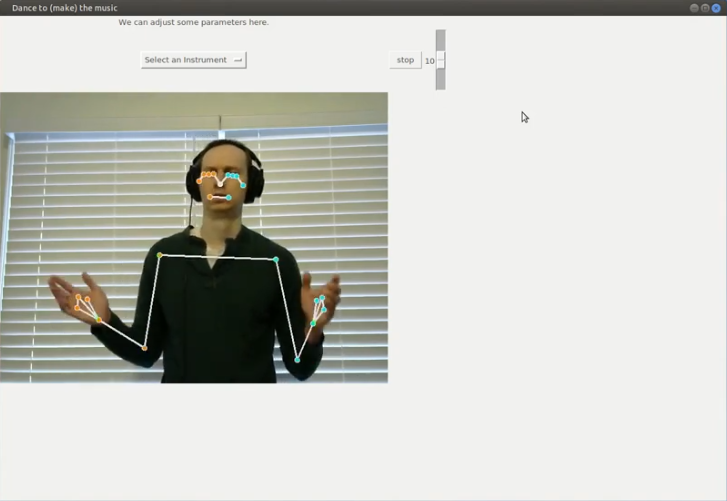

The GUI

The GUI, which is relatively simple, uses the tkinter package. The GUI is used to display the camera’s output, as well as including a selector widget to modify the MIDI instrument being used to render the sounds (which required a simple interrupt function to be written) and a slider widget to adjust the sensitivity of the percussion to the subject’s wrist motions, as well as a stop button to end the program and free the camera and virtual MIDI device. Rather than using the more traditional tkinter-based loop, the window is updated and parameters are polled during a loop controlled by the camera’s acquisition process.

The Sounds

The sounds are generated using the program “fluidsynth,” and specifically a python wrapper named pyfluidsynth found in the “mingus” package. Fluidsynth itself is a c-based program for control of a virtual midi device, implementing essentially all of the MIDI standard options. Not all controls were ported into the pyfluidsynth wrapper; for this project, I needed to adjust the “pitch wheel sensitivity,” to allow the program to “bend” the tone of notes over a much larger range than is typical. Although this is doable in fluidsynth, it had not been added to the pyfluidsynth wrapper. Luckily, examining the library’s code showed that it was just wrapping the base fluidsynth commands in a cfunc wrapper, so with minimal effort I was able to manually add that command to the pyfluidsynth module, allowing me to access the pitch wheel sensitivity command of fluidsynth. I also had to include a command-line execution to link the fluidsynth process to the system sound; this is probably specific to linux.

The Computer Vision

The camera’s captured image is processed through mediapipe’s pose estimator. Mediapipe is an incredibly sophisticated package of pre-trained neural networks, created by Google, for computer vision problems. One of the sub-modules available is a pose estimator, which finds an estimate of a human pose in an image and returns the coordinates of different body parts such as the shoulders, eyes, wrists, fingers, etc. Although this is by far the most sophisticated part of the code, the package makes everything simple: I could essentially modify their simplest tutorial to get the behavior I wanted. The performance, even on my computer and without using a GPU, is genuinely baffling. I have no idea how they’ve done such a good job. The mediapipe pose estimate and the camera’s output are drawn onto the tkinter window.

The Kalman Filter

However, even with that sophisticated package, there are bound to be individual camera frames where the pose estimator fails, or incorrectly judges points to have jumped around all willy-nilly at the speed of light, and we all know no one dances that fast! To solve this problem, I implemented a simple Kalman Filter to estimate the true state of the body parts of interest. An additional benefit was that the Kalman estimator, which uses a constant acceleration model, will provide not just position (which is all we get from our mediapipe measurements) but also estimates for the state of velocity and acceleration for each tracked point. These derived quantities can then be used to trigger MIDI events: for example, the velocity of the shoulders adjusts the associated tones’ volume, and the acceleration of the wrists either upwards or downwards can trigger percussion events once a threshold magnitude is surpassed. Additionally, if no “pose” is returned by mediapipe, rather than simply keeping all parameters unchanged, we can create the illusion of still tracking (and the illusion of dynamicism) by propagating the state forward using the last-computed state transition matrix. This all works quite well, despite my having not bothered to take much time to fine-tune the various matrices used in the process, and assuming all covariances between points are zero (in reality, there are absolutely not – the location of my left shoulder has a relationship to the location of my right shoulder, since they are connected through my, you know, body; their uncertainties are therefore linked as well) .

In fact, there is great untapped potential in the Kalman filter: mediapipe returns a “visibility” parameter for a given point, which amounts to a confidence. One could consider using this confidence to adjust the Kalman gain (the ratio by which the observed measurements and the estimated state are combined to create a new estimated state). However, for the current project, the basic Kalman filter I implemented meets the needs well.

Kalman Implementation Note

Note that for both updating and propagating the state, we must send our Kalman filter a time delta: because we are not synchronized to a hardware clock, dt may be different for different updates, so we can’t set this when we first initialize our matrices, as it shown in most examples. This is possible by using sympy and then it’s own function lamdify, which allows use to create a function that will replace dt in the sympy matrix and return to use a numpy array ready to use with the rest of our numpy arrays; we simply need to call this function at each update or propagate call.

The Future

In the future, it would be fun to extend the functionality by allowing more flexibility regarding what points correspond to what MIDI events, either by allowing the user to “wire up” the connections themselves, or, in an even more audacious plan, using machine learning to generate wires by training the connections on paired music/dance routines. Think about how cool this could be: train on video of a ballet dancer; the algorithm learns what motions correspond to what in the music, then you use those connections on someone’s movements. Alternatively, once you’ve learned the connection between movement and music, you generate the “perfect” dance to a given song. This idea, however, is clearly beyond the scope of a CS50 project.